Reality is not what it seems by Carlo Rovelli

Shattering intuitions about space, time, and the nature of reality 🌍

If in some cataclysm all scientific knowledge were to be destroyed and only one sentence passed on to the next generation of creatures, what statement would contain the most information in the fewest words? I believe it is the atomic hypothesis — all things are made of atoms, little particles that move around in perpetual motion, attracting each other when they are a little distance apart, but repelling upon being squeezed into one another.

Zeno’s Paradox

The most famous of Zeno’s paradoxes is presented in the form of a brief fable: the tortoise challenge. The tortoise challenges Achilles to a race, starting out with a 10 m advantage. Will Achilles manage to catch up with the tortoise? Zeno argues that rigorous logic dictates that he will never be able to do so. Before catching up, in effect, Achilles needs to cover 10 m, and in order to do this he will take a certain amount of time. During this time the tortoise will still have advanced a few centimeters. To cover these centimeters Achilles will have to take a little more time, but meanwhile the tortoise will have advanced further, and so on to infinity. Achilles therefore requires an infinite number of intervals to reach the tortoise — an infinite number of times.

At the end you will obtain an infinite number of small pieces of string. The sum of these, however, will be finite, because they can only add up to the length of the original piece of string. An infinite number of strings can make a finite string, and an infinite number of increasingly short times may make a finite time. The hero, even if he will have to cover an infinite number of ever-smaller distances, will take a finite time to do so and will end up catching the tortoise.

The solution lies in the idea of the continuum: arbitrarily small times may exist, an infinite number of which make up a finite time.

Brownian Motion

If we observe attentively very small particles, such as a speck of dust or a grain of pollen suspended in still air or in a liquid, we see them tremble and dance. Pushed by this trembling, they move randomly, zigzagging, and so they drift slowly, gradually moving away from their starting point. This motion of particles in a fluid is called Brownian motion, after a biologist who described it in detail in the 19th century.

There are an enormous number of molecules of air. On average, as many hit the granule from the left as those that hit it from the right. If the air’s molecules were infinitely small and infinitely numerous, the effect of collisions from the right and from the left would cancel out at each instant, and the granule would not move. But the finite size of molecules — the fact that they are present in finite rather than infinite number — causes there to be fluctuations. That is to say, the collisions never balance out exactly; they only balance out on average.

Maxwell’s Laws

He computes the speed at which the undulations of Faraday’s lines move, and the results turn out to be the same as for light. Why? Maxwell understands: because light is nothing other than this rapid trembling of Faraday’s lines!

What is color? Put simply, it is the frequency, or the speed of oscillation, of the electromagnetic wave that light is. If the wave vibrates more rapidly, the light is bluer; if it vibrates a little more slowly, the light is redder.

The Key Theories

The deepening of our understanding of the world is based on two theories: general relativity and quantum mechanics. Both demand a daring revaluation of our conventional ideas about the world — space and time in relativity, matter and energy in quantum theory.

Einstein in 1905: Theory of Relativity

Between the past and the future of an event (for example, between the past and the future of you, where you are, and the moment in which you are reading), there exists an intermediate zone, an expanded present — a zone that is neither past nor future. The duration of this intermediate zone, which is neither in your past nor in your future, is very small and depends on where an event takes place relative to you. The greater the distance of the event from you, the longer the duration of the extended present.

On the Moon, the duration of the expanded present is a few seconds, and on Mars it is a quarter of an hour. This means we can say that on Mars there are events that at this precise moment have already happened, events that are yet to happen, but also a quarter of an hour during which things occur that are neither in our past nor in our future.

In technical terms, we say that Einstein had understood that “absolute simultaneity” does not exist: there is no collection of events in the universe which exists “now.”

Spacetime: the set of all past and future events, but also those that are neither past nor future; these do not form a single instant — they have themselves a duration.

In the Andromeda galaxy, the duration of this expanded present is 2 million years. Everything that happens during these two million years is neither past nor future with respect to ourselves.

A result of this restructuring is that, as space and time fuse together in a single concept of spacetime, so the electric field and the magnetic field fuse together in the same way, merging into a single entity which today we call the electromagnetic field.

The concepts of mass and energy become combined in the same way as time and space, and electric and magnetic fields, are fused together in the new mechanics.

This implies that mass by itself is not conserved, and energy as it was understood at the time is not independently conserved either. One may be transformed into the other: only one single law of conservation exists, not two. What is conserved is the sum of mass and energy, not each separately. Processes must exist that transform energy into mass or mass into energy. The result is the celebrated formula E = mc².

The present is like the flatness of the Earth: an illusion. We imagine a flat Earth because of the limitations of our senses, because we cannot see much beyond our noses. Had our brain and our senses been more precise, had we easily perceived time in nanoseconds, we would never have made up the idea of a present extending everywhere. We would have easily recognized the intermediate zone between our past and future. We would have realized that saying “here and now” makes sense, but that saying “now” to designate events happening throughout the universe makes no sense.

Einstein in 1915

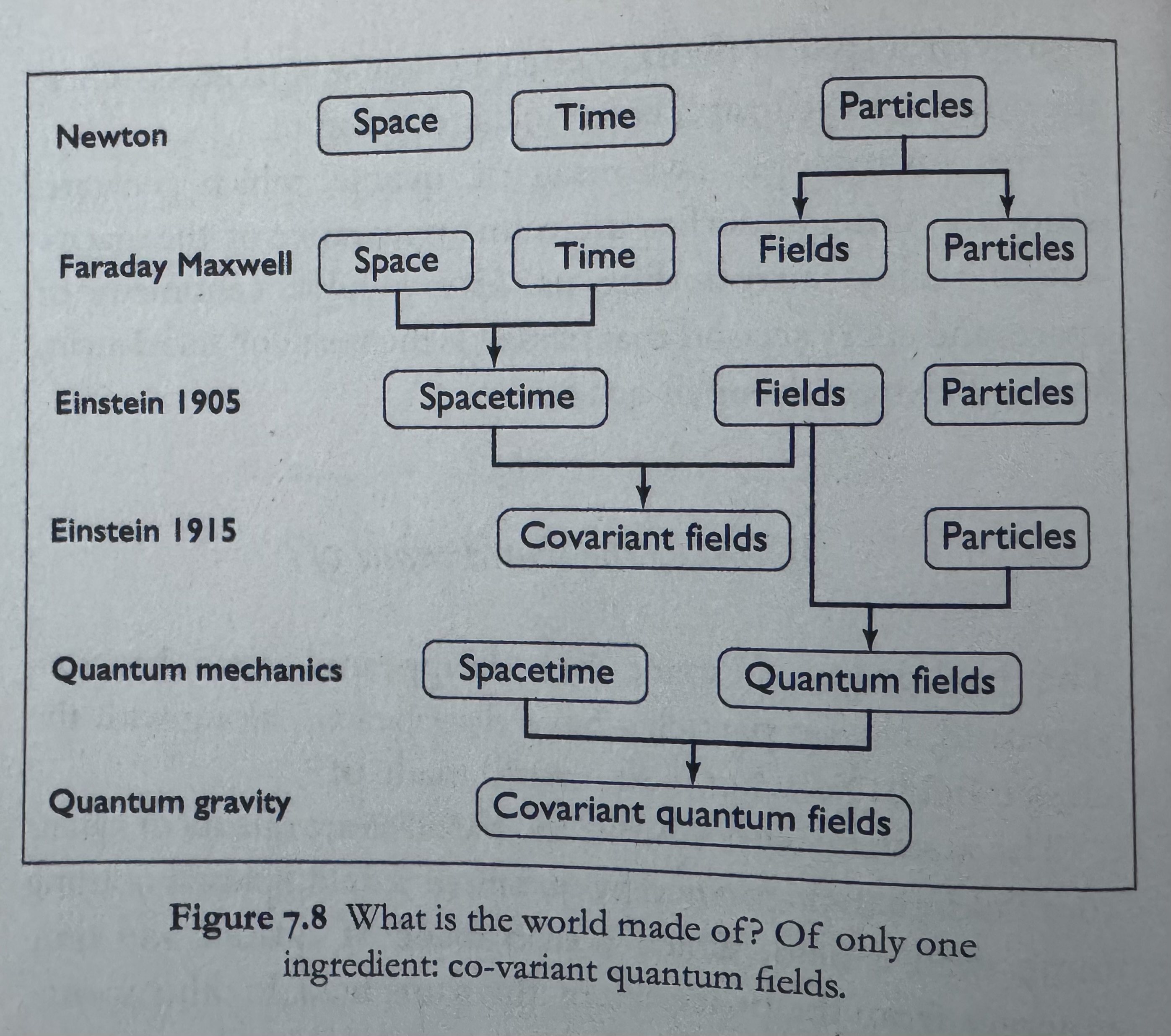

The world is not made of space + particles + electromagnetic field + gravitational field. The world is made up of particles + fields, and nothing else. There is no need to add space as an extra ingredient. Newton’s space is the gravitational field. Or vice versa, which amounts to saying the same thing: the gravitational field is space.

The Sun bends space around itself, and the Earth does not circle around it drawn by a mysterious distant force, but runs straight in a space that inclines. It is like a bead which rolls in a funnel: there are no mysterious forces generated by the center of the funnel; it is the curved nature of the funnel wall which guides the rotation of the bead. Planets revolve and things fall because space around them is curved.

Riemann’s result was that the properties of a curved space in any dimension are described by a particular mathematical object which we now call Riemann curvature and indicate with the letter R. In a landscape of plains, hills, and mountains, the curvature R of the surface is zero on plains, which are flat — that is, without curvature — and different from zero where there are valleys and hills. It is maximum where there are pointed peaks of mountains, that is to say, where the ground is least flat or most curved. Riemann’s math: an equation where R is proportional to the energy of matter. In other words, spacetime curves more where there is matter.

But it is not only space that curves; time does too. Einstein predicts that time on Earth passes more quickly at higher altitude and more slowly at lower altitude. Place a watch on the floor and another on a table: the one on the floor registers less passing of time than the one on the table. Why? Because time is not universal and fixed; it is something which expands and shrinks according to the vicinity of masses. The Earth, like all masses, distorts spacetime, slowing time down in its vicinity.

There are two absurd entities: the absurdity of an infinite space and the absurdity of a universe with a fixed border, and there did not seem to be any reasonable choice between them. But Einstein finds that the universe can be finite and at the same time have no boundary. How? Just as the surface of the Earth is finite but does not have a boundary — there is nowhere it ends. This can happen naturally enough if something like the surface of the Earth is curved. And in the theory of general relativity, of course, three-dimensional space can also be curved. Consequently, our universe can be finite but borderless.

The leap made by Einstein is unparalleled: spacetime is a field; the world is made up of only fields and particles; space and time are not something else, something different from the rest of nature — they are just a field among others.

Quanta

Max Planck in 1900 tries to compute the amount of electromagnetic waves in equilibrium in a hot box. He assumes that the electric field is distributed in quanta — that is to say, in small packets; light bricks of energy. The size of the packets, he assumes, depends on the frequency of the electromagnetic waves. For waves of frequency f, every quantum, or every packet, has energy E = hf.

In 1905, Einstein considers a phenomenon that had been recently observed: the photoelectric effect. There are substances that generate a weak electric current when struck by light. It seems reasonable to expect that if the energy of light is scarce — namely, if the light is dim — the phenomenon would not take place, and that it would take place when energy is sufficient, namely when light is bright. But it isn’t like this: what is observed is that the phenomenon happens only if the frequency of light is high and does not happen if the frequency is low. That is to say, it happens or doesn’t happen depending on the color of the light rather than its intensity. There is no way of making sense of this with standard physics. If, as in Planck’s hypothesis, the energy of each grain is determined by frequency, the phenomenon will occur only if the frequency is sufficiently high — that is to say, if individual grains of energy are sufficiently large — independent of the total amount of energy that is around.

Today we call these packets of energy photons, from the Greek word for light. Photons are light’s quanta. There is a clear relationship between Einstein’s work on Brownian motion and quanta of light, both completed in 1905. In the first, Einstein had managed to find a demonstration of the atomic hypothesis — that is to say, of the granular structure of matter. In the second, he extends this to light: light must have a granular structure as well.

Studying the light emitted by atoms, it is apparent that substances have specific colors. Since color is the frequency of light, light is emitted by substances at certain fixed frequencies. The set of frequencies that characterizes a given substance is known as the spectrum of that substance.

In Newton’s mechanics, an electron can revolve around its nucleus at any speed and hence emit light at any frequency. But then why does the light emitted by an atom not contain all colors, but just a few particular ones? Why are atomic spectra not a continuum of colors, instead of just a few separate lines? Why, in technical parlance, are these discrete instead of continuous?

Once again the key is granularity — but not now for the energy of light, but rather the energy of electrons in the atom. Bohr makes the hypothesis that electrons can exist only at certain special distances from the nucleus — that is, only on certain particular orbits, the scale of which is determined by Planck’s constant h — and that electrons can leap between one orbit with a permitted energy to another. These are the famous quantum leaps. The frequency at which the electron moves on these orbits determines the frequency of the emitted light. Since only certain orbits are allowed, it follows that only certain frequencies are emitted.

Emergence of the Copenhagen Theory

What if the electron could be something that manifests itself only when it interacts, when it collides with something else, and that between one interaction and another it had no precise position? What if always having a precise position is something which is acquired only when one is substantial enough? Heisenberg comes up with a fundamental description of the movement of particles in which they are described not by their position at every moment, but only by their position at particular instants: the instants in which they interact with something else.

Electrons don’t always exist. They exist when they interact. They materialize in a place when they collide with something else. The quantum leaps from one orbit to another constitute their way of being real: an electron is a combination of leaps from one interaction to another. When nothing disturbs it, an electron does not exist in any place.

Dirac’s quantum mechanics is the mathematical theory used by any engineer, chemist, or molecular biologist. In it, every object is defined by an abstract space (Hilbert space) and has no property in itself apart from those that are unchanging, such as mass. Its position and velocity, its angular momentum and its electrical potential, and so on, acquire reality only when it collides — interacts — with another object. It is not just its position that is undefined, as Heisenberg had recognized: no variable of the object is defined between one interaction and the next. The relational aspect of the theory becomes universal.

Dirac provides the general method to compute the set of values that physical variables can take (these are the eigenvalues of the operator associated with the physical variable in question; the key equation is the eigenvalue equation). Today we call the set of particular values which a variable may assume the spectrum of that variable, by analogy with the spectra into which the light of elements decomposes — the first manifestation of the phenomenon.

The theory also gives information on which value of the spectrum will manifest itself in the next interaction, but only in the form of probabilities. Quantum mechanics brings probabilities to the heart of the evolution of things. This indeterminacy is the third cornerstone of quantum mechanics: the discovery that chance operates at the atomic level. If we have sufficient information about the initial data and if we can make calculations, quantum mechanics allows us to calculate only the probabilities of an event. This absence of determinism at small scales is intrinsic to nature. The determinism of the macroscopic world is due only to the fact that microscopic randomness cancels out on average, leaving only fluctuations too minute for us to perceive in everyday life.

Dirac’s quantum mechanics allows us to do two things. (1) The first is to calculate which values a physical variable may assume. This is called the spectrum of a variable; it captures the granular nature of things. When an object (atom, electromagnetic field, molecule, pendulum, stone, star) interacts with something else, the values computed are those which its variables can assume in the interaction. (2) The second thing that Dirac’s quantum mechanics allows us to do is to compute the probability that this or that value of a variable appears in the next interaction. This is called the calculation of an amplitude of transition. (3) Probability expresses the third feature of the theory: indeterminacy — the fact that it does not give unique predictions, only probabilistic ones.

This is Dirac’s quantum mechanics: a recipe for calculating the spectra of variables, and a recipe for calculating the probability that one in the spectrum will appear during an interaction.

Dirac discovers an ulterior profound simplification of our description of nature: the convergence of the notion of particles used by Newton and the notion of fields introduced by Faraday. The equations of Dirac determine the values a variable can take. Applied to the energy of Faraday’s lines, they tell us that this energy can only take on certain values and not others. Since the energy of the electromagnetic field can only take on certain values, the field behaves like a set of packets of energy. These are precisely the quanta of energy introduced by Planck and Einstein 30 years earlier. The circle closes and the story is complete. The equations of the theory written by Dirac account for the nature of light which Planck and Einstein had intuited.

The general form of quantum theory compatible with special relativity is thus called quantum field theory, and it forms the basis of today’s particle physics. Particles are quanta of a field, just as photons are quanta of light. All fields display a granular structure in their interactions.

Quantum mechanics, with its fields and particles, offers today a spectacularly effective description of nature. The world is not made up of fields and particles, but of a single type of entity: the quantum field. There are no longer particles which move in space with the passage of time, but quantum fields whose elementary events happen in spacetime. The world is strange but simple.

Quantum mechanics has taught us the nature of things: granularity, indeterminacy, and the relational structure of the world.

Quanta 1: Information Is Finite

The granularity of matter and light is at the heart of quantum theory. We make measurements on a physical system and find that the system is in a particular state. For instance, we measure the amplitude of the oscillations of a pendulum and find that it has a certain value, say somewhere between 5 and 6 cm. Before quantum mechanics, we would have said that since there are an infinite number of possible values between 5 and 6 cm, there are infinite possible states of motion in which the pendulum could find itself. Quantum mechanics tells us that between 5 and 6 cm there is a finite number of possible values of the amplitude; hence our missing information about the pendulum is finite.

Quanta 2: Indeterminacy

How do we compute the probability that an electron in a certain initial position A will reappear after a given time in one or another final position B? In the 1950s, Richard Feynman suggests a method of making this calculation. Consider all possible trajectories from A to B — that is to say, all possible trajectories the electron can follow. Each trajectory determines a number. The probability is obtained from the sum of all of these numbers. This technique for computing the probability of a quantum event is called Feynman’s sum over paths, or Feynman’s integral.

Quanta 3: Reality Is Relational

The theory does not describe things as they are: it describes how things occur and how they interact with each other. It doesn’t describe where there is a particle, but how the particle shows itself to others. The world of existent things is reduced to a realm of possible interactions. Reality is reduced to interaction. Reality is reduced to relation.

Galileo understood that speed is not an object of its own: it is the property of motion of an object with respect to another object. Einstein extended relativity to time: we can say that two events are simultaneous only relative to a given motion. Quantum mechanics extends this relativity in a radical way: all variable aspects of an object exist only in relation to other objects. It is only in interactions that nature draws the world.

To summarize, the discovery of three features of the world:

- Granularity: the information in the state of a system is finite and limited by Planck’s constant.

- Indeterminacy: the future is not determined unequivocally by the past. Even the most rigid regularities we see are ultimately statistical.

- Relationality: the events of nature are always interactions. All events of a system occur in relation to another system.

Properties of things manifest themselves in a granular manner only in the moment of interaction — that is to say, at the edges of the processes — and are such only in relation to other things. They cannot be predicted in an unequivocal way, but only in a probabilistic one.

What Is Unknown in Current Physics?

Spacetime Is Quantum

In most situations we can neglect quantum mechanics or general relativity or both. The Moon is too large to be sensitive to minute quantum granularity, so we can forget the quanta when describing its movements. On the other hand, an atom is too light to cause space to curve to a significant degree, and when we describe it we forget the curvature of space. But there are situations where both curvature of space and quantum granularity matter, and for those we do not yet have a physics that works.

Time Does Not Exist

Time does not pass in the same way everywhere in the world. In some places it flows more quickly, in others more slowly. The closer you get to the Earth, where gravity is more intense, the slower time passes.

Think of time as if there were a great cosmic clock that marks the life of the universe. We have known for more than a century that we must think of time instead as a localized phenomenon: every object in the universe has its own time, running at a pace determined by the local gravitational field.

But even this notion of localized time no longer works when we take the quantum nature of the field into account. Quantum events are no longer ordered by the passage of time at the Planck scale. Time, in a sense, ceases to exist.

What does it mean to say that time does not exist?

First, the absence of the variable time from the fundamental equations does not imply that everything is immobile and that change does not happen. On the contrary, it means that change is ubiquitous. Only: elementary processes cannot be ordered in a succession of instants. The passing of time is intrinsic to the world; it is born of the world itself, out of the relations between quantum events which are the world and which themselves generate their own time.

It means that we in reality never measure time itself: we always measure physical variables A, B, C, … and compare one variable with another — that is to say, we measure the functions A(B), B(C), C(A), … and so on. We can count how many beats for each oscillation, how many oscillations for every tick of my stopwatch, how many ticks of my stopwatch between intervals of the clock on the bell tower, …

We must learn to think of the world not as changes in time but in some other way. Things change only in relation to one another. At a fundamental level, there is no time. Our sense of the common passage of time is only an approximation which holds at our macroscopic scale. It derives from the fact that we perceive the world in a coarse-grained fashion.

What Is Our World Made Of?